The Spotter Pro app aims to reduce whale deaths in shipping lanes through crowdsourced reports.

by L. Clark Tate

April 15, 2014—Surely a world full of iPhone-smartened citizens can pool our collective brainpower to protect our own environment. With all that combined power, Captain Planet is sure to pop up somewhere, right?

While we may not be there yet, the clever folks at Whale Aware, a loose collective formed by Point Blue, San Francisco area marine sanctuaries, Conserve.IO and EarthNC to promote ocean protection, are working on it. The Spotter Pro app, available on the iTunes App Store, is crowdsourcing science to tackle the crown jewel of environmental conservation: saving the whales.

Whales have a world of problems, starting with warming, acidifying waters and humanity’s collective clanging racket. Slow-moving whales – humpbacks, fins, grays and blues – must brave yet another hazard: really big ships. The bustling ports of Oakland and L.A., which are surrounded by California’s uber-productive National Marine Sanctuary system (Cordell Bank, Gulf of the Farallones, Monterey Bay and Channel Islands), bring 100,000-ton container ships a little too close to marine life for comfort on occasion.

__________

Read about the 2013 introduction of new rules for California shipping lanes in Whale Crossing

Read NRDC: Noisy Oceans Harming Wildlife

__________

“It’s a classic multiple-use issue,” says Michael Carver, Deputy Superintendent of Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary and Whale Aware partner. Between 1988 and 2012, 100 whale-ship “strikes” were documented in California’s coastal waters, according to NOAA. In 2010 alone, ship strikes killed five whales (two blues, one humpback, and two fins).

Whale Danger Zone

Yep, aquatic megafauna roadkill. And the number of whales found draped across a ship’s bow, washed up on beaches or floating along the coast with telltale ship strike wounds is likely much lower than the number of those actually struck.

Even if that number, 100, is fairly representative, it’s a big problem. These are fragile populations: humpbacks, fins and blues appear on the U.S. endangered species list. Fins and blues are also listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Blue whales are particularly vulnerable. These beautiful beasts have a Potential Biological Removal, or PBR (no relation to Pabst) level of three individuals. Translation: three blues can die outside of natural mortality rates without population stability suffering. By comparison grays, fins, and humpbacks have PBRs of 360, 16, and 11, respectively.

Unfortunately blues are also especially prone to ship strikes. In 2007 four blue whales were killed around So Cal’s Santa Barbara Channel. Based on their PBR, that’s a solid population hit. The blue whale’s natural stress response could be to blame. Their only non-human threat, the killer whale, drowns them. So when a blue whale is stressed out—say, when a large ship approaches—it surfaces, potentially right into the boat’s path. Not good.

Keeping Ships on The Straight And Narrow

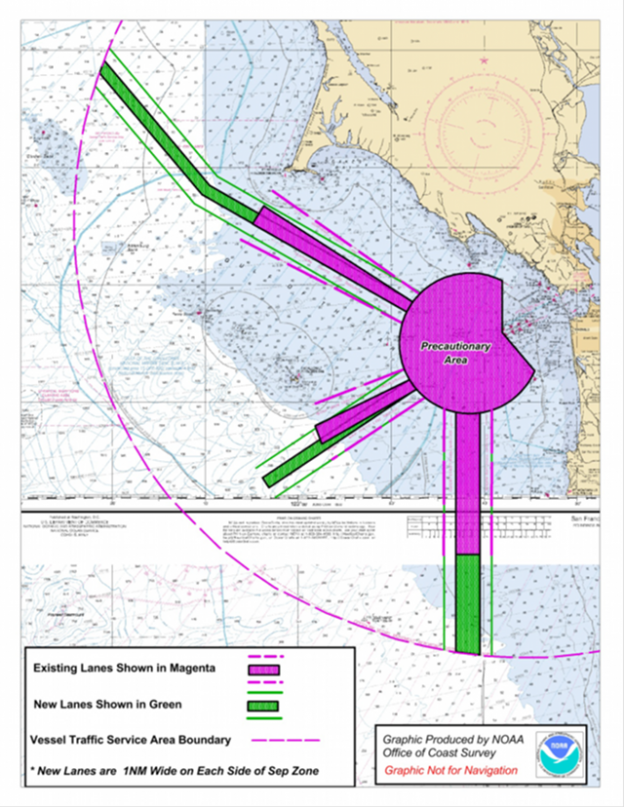

Last summer California took a huge step towards reducing unfortunate collisions between feeding, migrating whales and ginormous container ships. Sparked by a tragic accident between such a ship and a fishing boat off the coast of Point Reyes National Seashore, the Coast Guard launched a Port Access Route Study in 2009 to take a hard look at shipping safety issues. Inspired by a 2007 lane shift and current speed limits in New England’s Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, Carver and his colleagues saw an incredible opportunity to reduce ship strikes to whales as well. A Joint Working Group of experts from the shipping industry and conservation and scientific communities, including Carver, worked with the Coast Guard on the study.

Happily, whales and fishing boats tend to frequent the same fishy waters, and one solution reduced the risk of being run down for both: narrow and lengthen shipping lanes beyond the borders of National Marine Sanctuaries. This straightforward shift reduces the risk of co-occurrence of whales and container ships substantially.

But Whale Aware’s not stopping there. They are now focusing on “dynamic management areas,” which actively slow or shift traffic around high-density pockets of whales. If whales and ships do have a run-in, reducing ship speed greatly reduces mortality rates. Slowing from 15-20 knots to somewhere between 8 and 12 can mean the difference between dead, injured or merely miffed.

Cetacean Crossings

To figure out where to position the dynamic management areas, Whale Aware needs to know where the whales are. Spotter Pro lets us (i.e., the crowd) help the Whale Aware researchers look. With all the iPhones strolling around the West Coast, that’s a lot of eyeballs.

What happens if you spot a lounging behemoth and report it with the app? A report of a whale glimpsed in a location well away from the shipping lanes—say, in Monterey Bay—will head to a database to inform later science, like the mapping of whale migrations. “Ideally we will be able to watch the whales in near-real time up and down the coast thanks to crowdsourced data,” says Carver.

If yours joins a cluster of reported sightings near shipping traffic, you might just launch a full-scale whale safety mission. A burst of whale alerts sends Carver up in a Coast Guard chopper to verify the sighting and could result in a broadcasted request for shipping traffic to slow or shift lanes. In short, you could save a whale. Now there’s some power. Forget Captain Planet—that’s straight James Bond.

And what’s more, ships are slowing down, voluntarily.

This is a pretty freaking big deal. There are no regulations that require them to comply with these requests. The logistical challenges of getting a ship into port on schedule are significant, and missing a time slot means missing out on big bucks. So why is the shipping industry willing to work with the whales on this one?

According to Carver it’s not that much of a stretch. “They spend their lives as seafarers because they love the ocean. They don’t want to hit whales, either.”

Kudos to the shipping industry. We salute your whale lifesaving cooperation.

Science in Our Hands

But will it work? “Can we get the data at a robust enough level to implement a dynamic management area that we know will have a conservation benefit?” asks Carver. “That’s the pivotal question.” What he does know is that these are marine sanctuaries, and “protecting endangered species is a priority for NOAA.”

Though coverage of the shipping lanes is pretty solid, Spotter Pro hasn’t exactly taken off just yet. So far pretty much only hardcore science nerds, conservationists, whale watchers and shipping industry participants are using it. Carver admits that it’s a little complicated and data-intensive for the general public (we’re secretly hoping that the Hilltromper public proves him wrong). Spoiler: a new, simplified app is scheduled to launch late spring/early summer, so heads up.

Saving the whales—of course there’s an app for that. Now go use it.

Category: