This is an excerpt from the opening essay of Bridget A. Lyons’ new book, Entwined: Dispatches from the Intersection of Species, published July 20 by Texas A&M University Press, and available for purchase now.

Lyons will appear at 7pm Tuesday, July 22, at Bookshop Santa Cruz along with the author Josie Iselin for an event: Celebrating The Intersection of Natural History, Writing, And Art. For more info about the event, follow this link.

By Bridget A. Lyons

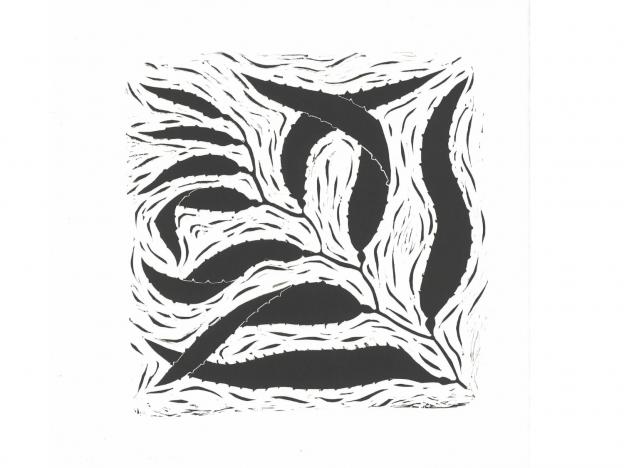

I spend a lot of time sitting up on my surfboard, watching the surface of the Monterey Bay for the darkened wave faces that make my heart beat faster. In between sets, I pull a strand of kelp from the water and play with it. If it’s a piece of bull kelp, the kind with the single stalk that’s an inch or two in diameter, I grab it somewhere below the tennis-ball-sized air bladder and whip it around like a cellulose lasso. If it’s a fragment of giant kelp, I lay the more delicate array on my board to admire its alternating patterns of blades and stipes—structures that would be called leaves and stems on a terrestrial plant but earn unique names on a piece of aquatic macroalgae. Sometimes, I’ll wrap a braid of giant kelp around my wrist so that its air bladders— smaller ones that resemble the bulb of a scallion—dangle like charms from my mermaid’s bracelet, adding some flair to my otherwise bland black neoprene outfit. These will be the most contented moments of my day, these extended breaks from my maddening habit of assessing my own worth and the value of everything around me.

The texture of wet kelp is like nothing else I know. The obvious word to describe it would be “slimy,” but that doesn’t quite work for me. Kelp doesn’t feel like uncooked egg or earthworm skin. It is much firmer and slicker, yet still cool and wet to the touch. Unlike fish or slugs, it leaves you with no residue. Once you have pulled a stiff stalk of the genus Laminaria through your fingertips, all you can say is that it feels like kelp. It is totally alien and slightly creepy, and I love it for its uniqueness.

When I spin my board around to paddle for a wave, I fling my temporary accessory back into the water. It continues to float there, always, thanks to its pneumatocysts—the air bladders—that keep much of it on the surface. There, the kelp accesses the sun’s rays to participate in photosynthesis, the action that once caused scientists to put it in the plant kingdom, despite its aquatic home and lack of a root system. When three more kingdoms were added to the world of living things, kelp was reassigned to the one called eukaryotic algae, a wildly diverse gang of organisms that includes single-celled protozoans in addition to macroalgae.

It’s good to know that we can rearrange our classification of things from time to time. It gives me hope that the world might be able to reevaluate me, or that I might be able to reevaluate myself.

I live three blocks from the spot where I commune with kelp. Because I live alone and work in the gig economy, I can surf just about anytime I want to. Because I live alone and work in the gig economy, I suffer from some guilt about surfing whenever I want to. I wonder if I am being productive enough, if I am doing what society expects me to, if I am squandering the evolutionary advantages of my big brain or wasting the planetary resources required to keep me breathing. At the dinner table, my father often talked about the importance of making a contribution to society. I was never quite sure if that contribution was supposed to be artistic or scientific or something else, and I was too intimidated to ask. I also wondered how big the contribution had to be to qualify.

Did creating a single painting or poem count? Or teaching a successful class? Producing a good-looking newsletter? How about making the cashier at the supermarket smile? I’ve done all of those things. Most days, I don’t think they’re

enough.

It’s hard to find information about kelp that isn’t focused on all the good it does for other species. When I first started clicking on marine biology websites, I was simply trying to find out the names and characteristics of the various types of seaweed I was getting caught up in. But as they became my more regular companions, I wanted to acquire some cool facts about them. Things like “giant kelp can grow as fast as 10–12 inches per day,” “kelp can stretch up to 40% of its length before it breaks,” and “bull kelp’s air bladders contain up to 10% carbon monoxide.” I learned that giant kelp—the garland that gets wound around the leash of my surfboard—prefers calm conditions where it outcompetes its cousin for sunlight. Burly bull kelp (which I discovered is also called “bullwhip kelp”—apparently, I am not the only one to have enjoyed hurling it over my head) does better in turbulent waters. In coastal California, where I live, these two vie for predominant species status. Among kelp, that is.

Apart from this smattering of details, I was mostly inundated with information about how important kelp is to other species that sit farther up on the supposed evolutionary ladder. As a literal aquatic forest, kelp conglomerations have been documented as providing shelter for over eight hundred species of marine animals, from invertebrates and fish to the central coast’s beloved sea otters and sea lions. Whether dead kelp sinks to the bottom of the ocean or washes up onshore, it becomes a source of food for other living things or nutrients for the ocean itself. And then, of course, there are the human uses. Fisheries are healthier where kelp thrives. People eat seaweed directly. We extract compounds from it that appear in shampoo, pudding, soymilk, toothpaste, fertilizer, nail polish, ketchup, and a host of other commonly used items. Colonies of kelp soften the effects of coastal shorebreak. They foster human recreational activities like diving, bird-watching, and sportfishing. These resources told me that we should value this creature for the ways in which it serves the greater ecosystem—and, ultimately, us. But what about valuing it for just being? Does that count?

If the value of a living thing is based on how many services it provides to the larger ecosystem, I’m looking pretty worthless. I’m a forty-nine-year-old woman who has consciously chosen not to reproduce, so I’ve already failed to turn out one of the products I could have offered the world. I would be hard-pressed to say that I have a community depending on me, since no one on my block knows my name. And my income is low enough that I don’t pay taxes. I think this last one really bothers my father—a Wall Street guy who embraces the narrative of the self-made man. He’s a staunch opponent of social services and a vocal critic of anyone who, in his words, accepts hand-outs. “It’s important to be a producer, an earner, a contributor,” he always said. When he shouted, “Make yourself useful!” from his armchair, I assumed he was referring both to folding the laundry and to choosing a life path.

According to his definition of useful—one tied to output, income, status, and achievement—I am failing miserably. When I measure myself this way, I feel like a lone herring, lost beneath a bed of kelp, where the canopy of stipes, blades, and pneumatocysts completely obscures the sunlight.

Then again, when I picture that bed of kelp, I can’t help seeing how intertwined its elements are. Together, the stalks form a network of braided organisms that creates a fertile ecosystem—one in which each strand is an important part of the whole, one in which countless other creatures can find nourishment and protection. When this community undulates hypnotically with the incoming swell, I am captivated.

Bridget A. Lyons is a writer, editor and explorer living in Santa Cruz. Her book, 'Entwined: Dispatches from the Intersection of Species,' is available in local bookshops.

Category: